Food & Agriculture

CNEHJ has a Nurses’ Food & Agriculture Team that is helping to educate and engage nurses about farmworker health and safety.

There are a great many health and safety issues associated with the industrial food system that have caused both under- and overnourishment in the population, in addition to a host of occupational and environmental health risks. From the chemicals that the farmworkers are exposed to, to the hazardous conditions for assembly line workers in conventional meat packing and processing facilities, the products derived from these practices leave us with food choices that contribute to obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases.

As nurses, we have the opportunity to leverage our trusted voices to help shift the food system to safeguard and promote human and ecological health; increase access to nutritious food for everyone, especially our children; and help move us to more plant-based diets which are known to be healthier for people and the planet.

Diet Related Chronic Disease

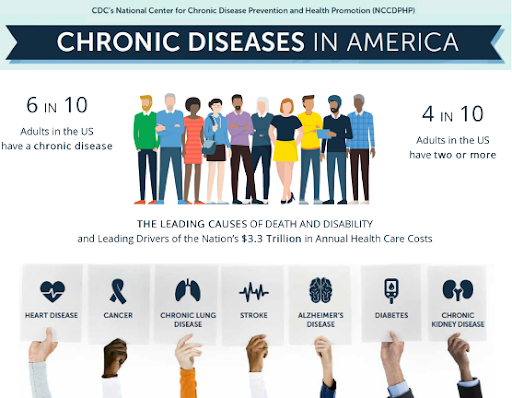

Our food system is broken and our patients are paying the price. The CDC reports that 6 in 10 people are now living with one chronic illness and 4 in 10 people with multiple – a state that significantly impacts activities of daily living and healthcare delivery. Having a chronic illness predisposes individuals to a variety of complicating health risk factors that include increased vulnerability to the worst outcomes of pandemics and other infectious diseases. Living with chronic disease is often compared to the burden of having a second full time job, taxing our productivity and threatening the health equity of future generations.

Nurses recognize the need to find upstream solutions to the chronic disease crisis.

Food (and Farming) is Medicine

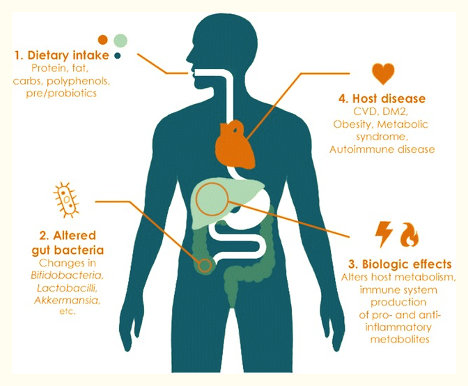

The human microbiome has trillions of microorganisms and 200 million protein encoded genes. Our gut microbiome is directly involved in immunity and disease prevention, but is also directly related to the microbial environment that we interact with most intimately.

Poor dietary choices alter the healthy balance of the microbiome, ultimately impairing the immune system and predisposing us to a wide variety of metabolic and autoimmune disorders.

The relative abundance – or deficit – of specific gut bacteria predicates inflammation, a key contributor to a chronic disease diagnosis. Just as food is medicine, farming can also be thought of in the same way. The human microbiome is a direct reflection of the composition of soil microbiology where all sources of life are derived, and as such, soil health and human health are intimately connected. The way we produce the food we eat is just as important to human health as the foods we choose to eat. Growing research comparing the two demonstrates a causal relationship, especially as it pertains to immunity, autoimmunity, and inflammation.

Nutrition Security

Food insecurity and chronic disease generally go hand in hand. Those who stand to benefit the most from a nutritious diet rich in polyphenols from fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, tend to have limited access to fresh foods and instead can only afford the least healthy food options available to them. This food is composed of highly processed “fast” foods ‒ the very products perpetuated by the industrial food system, which are widely distributed through food pantries, subsidies, and institutional nutrition programs. These nutrient-deficient choices result in concurrent micronutrient deficiencies and obesity in the population. Increasing access to not just enough calories, but the right kind of calories to support critical developmental periods, is the definition of nutrition security. Nurses can play a greater role in educating and guiding patients, and putting pressure on our institutional settings to improve the quality of nutrition for critically ill and vulnerable populations to improve health outcomes across the board.

Confined Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs)

Free stock photo, @Jo-AnneMcArthur IG

In terms of animal meat production, not all burgers are created equal. Across the US, the idealized farm has been replaced by Confined Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) which are the type of animal production facilities often referred to as “factory farms.” These facilities house over a thousand large animals, like beef cows or hogs, or tens of thousands of chickens. Over 50% of our meat in the US is derived from animals raised in CAFOs, even though they comprise only 5% of US farms. This gives a sense of the scale of their production.

There are a great many human and ecological health issues that arise with CAFOs. Despite the obvious ethical one regarding the inhumane way in which the animals are treated, non-therapeutic antibiotics are commonly used in these facilities to control the spread of disease that arises from crowded confinement. In addition, there are smell, air quality, and waste disposal challenges from the animal waste. It is estimated that 70% of all medically important antibiotics being sold in the US are for non-therapeutic animal use. This immense use of antibiotics that ultimately wind up in the soil and water, and have been found in the feces of workers in chicken houses, creates the conditions for the development of antibiotic resistant strains of pathogens. The Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy reported a 96% increase in sales of antibiotics for animal protein production between 2009 and 2015.

Nurses can help raise awareness about the threat of antibiotic resistance and the non-therapeutic usages of antibiotics in agriculture, and nurses can advocate for policies that address this issue.

Organic & Regenerative Farming

Choosing organically-grown foods remains one of the most important ways that we can protect ourselves from the harmful effects of chemical and industrial farming. Expanding organic agriculture across the state will help to bring down the costs of organic foods for everyone.

Farmers’ markets are a great place to find organic food at more affordable prices because purchasing occurs directly with the farmer and avoids the middle man, like distributors and retailers. CalFresh (California’s food stamp program) is partnering with farmers’ markets across California. In some instances, benefits are doubled resulting in increasing purchasing power. Find farmers’ markets near you that accept CalFresh benefits.

Regenerative farming has emerged as of late to replace the idea that simply “sustaining” vital resources, as is implied with the term sustainable agriculture, doesn’t go far enough to reverse our climate and ecological crisis. Rather, the focus needs to be on “regenerating” resources, which can be accomplished by effectively restoring biodiversity and promoting healthy practices across the entire ecosystem. Farming regeneratively also holds the potential to reduce agriculture’s contribution to greenhouse gas emissions. Regenerative organic agriculture places a high value on soil health, promoting animal welfare, and social fairness. A new regenerative organic certificiation, or ROC, is emerging to verify these practices for the public, but it is still in its infancy. There are a great variety of resources about regenerative organic agriculture including the Rodale Institute, which is a particularly good resource for nurses looking for evidence supporting the human and ecological value of this holistic approach to farming.

Pesticides

Just as many modern industries rely on toxic chemical inputs, so do many of our farms. While pesticides are often successful at combating their targeted agricultural pests, they are just as often creating human and ecological health risks (Donley, 2019).

The word “pesticide” is an umbrella term for a category of chemicals that are formulated, produced, and applied to harm a biological system. Pesticides are often further categorized by function. For instance, herbicides kill plants, insecticides kill or harm insects, fungicides kill fungi, and so on.

Collectively, pesticides have the potential to cause a very long list of health risks such as cancer, birth defects and other birth outcomes, reproductive health risks, neurological problems, and many more. It is, nevertheless, important for nurses to be specific when talking about pesticides and health risks because all pesticides do not cause all of the health risks. To remain evidence-based, nurses must determine the pesticide of concern and the specific evidence for that pesticide. The evidence in the literature is substantial and easily accessible.

The US Geological Survey (USGS) monitors ground and surface water for 76 pesticides and seven pesticide breakdown products. A survey found that 90% of streams and 50% of wells tested were positive for at least one pesticide (USGS, n.d.). Contaminated water has one of the greatest impacts on ecological health, creating risks to aquatic life and then, by extension, to the entire food chain within the natural world.

We can, and must, do better for our health and the health of the planet.

Plant-Based Diets Can Prevent and Reverse Chronic Metabolic Disorders

The Mediterranean diet is the the gold standard in the research literature demonstrating the innumerable health benefits of eating a well-balanced plant-based diet. It boasts a beneficial fatty acid profile, rich in both monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids, has high levels of polyphenols and other antioxidants, high fiber content, low glycemic carbohydrates, and has relatively greater intake of vegetable protein versus animal protein.

While the Mediterranean diet was one of the first plant-based diets, variations on vegetarianism and vegan diets have been emerging. In the last ten years, evidence indicates that plant-based diets have significant health advantages over diets with animal proteins. A plant-based diet results in better regulation of insulin, a healthier microbiome, and an optimal balance of nutrients that can effectively prevent or reverse the pathologies that lead to many chronic metabolic disorders.

Eating a nutritious diet means eating whole foods and avoiding highly processed foods. This dietary approach can effectively address the complex issues of obesity, chronic illness, and malnutrition and can lead to a healthier, more resilient, and more productive population.

In addition to the physiological costs of over-reliance on animal proteins, there are equally devastating environmental and societal costs. A recent report by the Rockefeller Foundation has calculated an annual cost of $2 trillion incurred by our current system ‒ a burden they note disproportionately affects communities of color.

USDA Certified Organic

In order to help the public choose produce (as well as meat/poultry) that has been grown/raised without the use of potentially harmful chemicals, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) has a “USDA Certified Organic” designation. USDA Certified Organic crops cannot be genetically modified organisms (GMO), the soil cannot have been augmented by sewage sludge, and no pesticides or synthetic fertilizers can have been used.

Any farmer or gardener can use a pest management approach that avoids toxic chemicals called Integrated Pest Management (IPM). The IPM Institute of America provides detailed information on how to engage in IPM strategies.

Nursing Actions Regarding Pesticides

- Nurses can help to increase demand for organic farming by choosing organic food products and by encouraging institutions, like hospitals, schools, and colleges/universities, to purchase organic food whenever possible. Health Care Without Harm has a wonderful Healthy Foods Program that can provide information and support to nurses who want to change hospital food purchasing policies.

- Nurses can advocate for pesticide policies that promote healthy crops, healthy people, and healthy ecosystems. CNEHJ works closely with the coalition Californians for Pesticide Reform to advocate for reduction/elimination of harmful pesticide use, farmworker/community “right to know” about pesticide exposures, and full-disclosure labeling for pesticides.

Meg Adelman, RN, BSN, MPH

Meg is a member of the Leadership Circle of CNEHJ and has been an advocate for implementing food as medicine in clinical, education, and policy arenas throughout her professional career. As Co-founder of Navitas Organics, a plant-based superfood company she and her husband have owned and operated since 2003, Meg is a champion for adopting lifestyle medicine ‒ the idea that our behaviors, not our genetics, determine the majority of our health outcomes. As a health educator, Meg has presented on this subject numerous times for continueing education (CE) workshops and webinars and co-chairs the Food & Ag Team for the California Nurses for Environmental Health & Justice.